This article was originally published in Norwegian in Ny Tid – By Rana Issa

Her father’s yellow car was the only place that Sana Yazigi felt safe enough to think. In Assad’s Syria, walls have ears and homes are not safe. Thinking is a crime in Syria, a crime punishable by kidnapping, torture, and jail. For its inhabitants, Syria is a kingdom of silence and of fear. In the first year or more, the revolution in Syria unfolded through a series of demonstrations and civil disobedience campaigns. The people took creative expression to great new heights. It was as if the Syrians who have been silent for more than 40 years could no longer stop thinking. The hyper production of cultural forms of expression, has googled in enormity. Last week, Oslo became a gathering point for some of the most important voices in Syria through a series of events organized by the newly established Syrian Peace Action Center, or SPACE, of which I am a co-founder with Zeina Bali and Murhaf Fares.

Our present moment witnesses the fragmentation of the Syrian people, and the dispersion of those voices all over the world. During this last week, we had to come to terms with the difficulties of articulating a coherent Syrian narrative owned by the people. Without such a narrative, our cause will be lost, our death will be certain, and our identity will no longer exist. But despite our local suffering, the Syrian narrative must come to terms with its globalization by not only challenging the master narratives of the International community, but also by connecting with the host communities where we now live to build solidarity networks. The people, whoever they are our strongest allies.

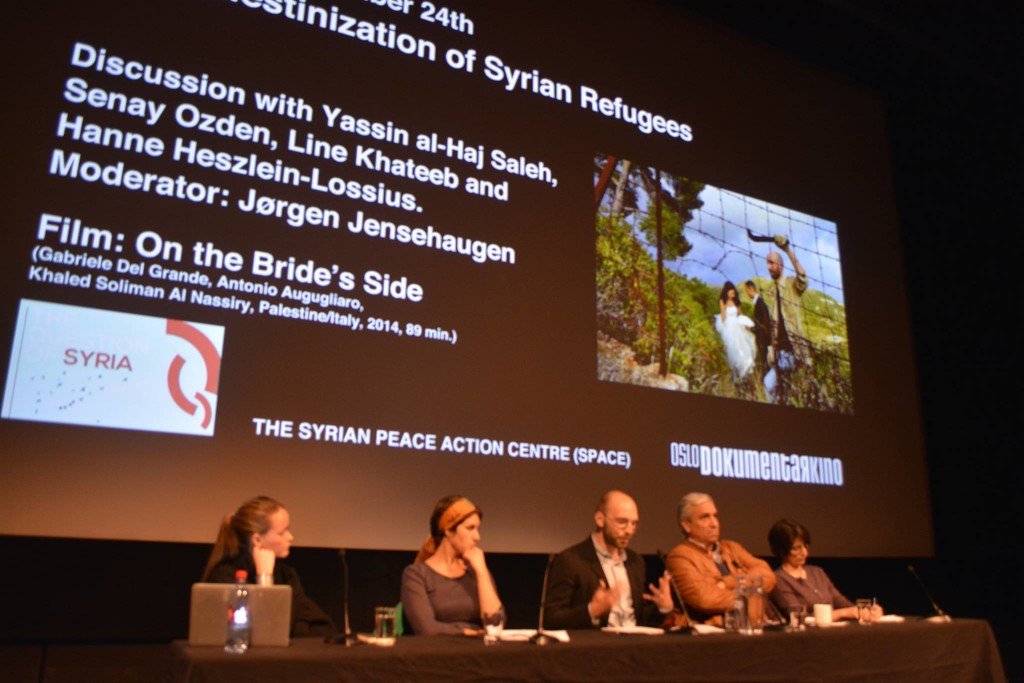

In Norway, we know we have allies, on all levels of political life, such as in the funding of important Syrian cultural and civil rights initiatives by Norwegian embassies, to local support of SPACE by Fritt Ord and others, to the grassroots level, represented last week by Hanne Heszlein-Lossius, a medical doctor from Bergen. Heszlein-Lossius who started the Facebook campaign “har du plass til en ekstra i hjemmet dit” took inspiration from Norwegian treatment of the Bosnians of the 90s . Through remembering our recent predecessors, Heszlein-Lossius explained to us, new comers, that there is an article in the law that is not being used in our case. She demanded that Syrian refugees be treated as a group and not as individual asylum seekers. This simple idea made us aware that our predicament is also connected to the legal refusal to see us as a people with a cause. We have become “palestinized” as the Syrian intellectual Yassin Haj Saleh writes. In that he meant we have been rendered invisible in the eyes of the international community.

Palestinization of Syrian Refugees – Cinemateket

Struggling against our disappearance from history, Sana Yazigi created the online cultural archive, creativememory.org. In her talk in Oslo, Yazigi shifted the date of the official start of the revolution from the accepted March 2011 to a month earlier, in February. She argues that February marks the first demonstration to take place in Damascus. After a police officer assaulted a merchant in Harika market, the people spontaneously gathered and began shouting “thieves, thieves.” Soon enough the minister of Interior arrived and threw the crowd in panic. He came out of his car and yelled, “is this a demonstration! Shame on you!” The people found themselves quickly obeying by shouting slogans in favor of the regime. The moment was too liminal, a tipping point that only one month after would break in open revolt in the Southeastern city of Daraa. Yazigi decentered the date of the revolution’s beginning. This decentered date reminded us that the revolt was inevitable. Often, Syrians are asked whether they regret the revolution. With Yazigi’s decentered beginning, we now have evidence that the situation in Syria was so dire before the revolution, and that people would have responded differently had the regime showed some leniency. Staying at home in the early days of 2011 would have been tantamount to suicide. People could no longer live in Syria; this is why they went out in self-defense. What I often wonder when someone asks this question is whether the incompetent ruler, turned war criminal, Bashar al-Assad ever regrets his criminal handling of the revolt. We will never know the answer, because none of the journalists who meet him will ever ask him the question.

The Creative Memory of the Syrian Revolution – Litteraturhuset

The Syrian need to express has not been limited to artists, and what they express is not always so comforting to see. In his lecture on the “filmer” videos of the Syrian revolution Zaher Omareen showed us a series of mobile phone films that have been documenting the barbarity of the regime against civilians. Arrests, torture and murder are all captured on camera to be uploaded for fast consumption on youtube. Through the harshness of those videos, Omareen approached the hardest part of our narrative, as we stare back at how helpless we have become in the face of Assad’s barrel bombs and torture cells. Omareen’s contribution demanded that we stare back at our horror, and open a dialogue with our death. We have to watch in loops the man holding the camera being shot dead, and we have to demand from him some answers about the future of our country. Filmers teach us that we have to accept that our identity is now in low resolution, not only pixelated as Omareen argued, but also only narrowly resolved with itself and with its surroundings.

Performing Democracy: Syrian Art Practices Today – Litteraturhuset

Five years on, our present is increasingly more difficult for us to accept. The theater director and dramaturge Mohammad al-Attar turned the struggle inwards, to the intimate structures of family life. Al-Attar who has been working with disenfranchised people since 2003 told us about the women who are paying the heaviest price of this revolt. The women, he reasoned have begun to take their own lives back. They no longer easily accept the tyranny of father, brother or son over their lives. And they have been leaving their homes to work, whether in his theater, or in the open market of labor in their countries of refuge. The men have been humiliated, which ironically opened a space for the women. The revolt has offset a crisis of masculinity, a crisis that women must seize to better their position. But this is a fragile and highly ironic gesture that remains structurally precarious because of abject poverty. In al-Attar’s work with these women, we see the power of theater to initiate dialogue. And dialogue is what most Syrians crave for these days. His theater helped some women break out of their shackles. And in her father’s yellow car, Yazigi also found a space for dialogue. And in Omareen’s macabre filmer genre, forcing death into dialogue becomes the most poignantly absurd representation of the Syrian predicament. If Syria teaches us anything at all, it is the simple idea that no thinking happens without dialogue.

*Rana Issa is a postdoc at the UiO working on Levantine literature and history and a board member of SPACE.