Troubled Waters: Images from the Arab World outdoor exhibition is part of Masahat festival for Arab Arts and Culture taking place during 20-25 September in different venues around Oslo!

During the festival week 20-25 September, you will be able to experience the exhibition in different outdoor areas around Oslo. See here the map of the exhibition. The four locations are Kristparken, the green area around Kulturkirken Jakob, Kubaparken, and Bjørvika.

Troubled Waters: Images from the Arab World is an outdoor exhibition addressing the prospects of just transitions and climate justice given the environmental degradation affecting the Arab world today. It speaks about the flow of capital and people and the hierarchy of geographies between a Global North and a Global South, determined through modern financial, industrial, and extractive coloniality. Photo essays produced by four Arab photographers –Nadia Bseiso (Jordan), Tamara Saadé (Lebanon), Roger Anis (Egypt) and Seif Kousmate (Morocco)– will occupy four locations in the city of Oslo, creating an inevitable discussion between imagined landscapes, the reality of Oslo, and counterpart cities in the south. Despite these North and Southern cities having no immediate formal correlation, at first sight, it shows the contrasts between environments while encouraging a rethinking of a shared responsibility towards the Planet.

People from the Arab world have periodically taken to the streets in the past decades due to degradation producing poverty through economies of extractivism carried out by colonial and authoritarian powers. The exhibition Troubled Waters, part of Masahat’s annual festival for Arab arts and culture, seeks to cultivate an arena for mutual inspiration and exchange amongst Norwegian and Arab scholars, activists, and artists who are concerned with ecological politics in order to contribute to shaping tools capable of carrying solidaristic concerns to tear down colonial structures, authoritarian regimes and their ideology.

The installations for the exhibition are designed by artist Frido Evers.

The exhibition is produced by Masahat in collaboration with Fotogalleriet, AFAC and Khartoum Contemporary Art Center. The project has been made possible through grants and support from Oslo City, Fritt Ord, KORO (Public Arts Norway), and Arts Council Norway.

Photo credit: Roger Anis, “Oh Mysterious Nile… Will You Be Immortal!”, Egypt, Arab Documentary Photography Program 2020.

يسعى المعرض الفوتوغرافي مياه عكرة: صور من العالم العربي إلى مسائلة أفق تحقيق عدالة مناخية في ظل التدهور البيئي في العالم العربي. يتحدث المعرض عن تدفق رأس المال والبشر وهرمية الجغرافيات بين دول الشمال والجنوب، يحدد مسارها بنى كولونيالية اقتصادية، صناعية واستخراجية.

ستحتل أربعة مشاريع فوتوغرافية لأربعة مصورين –نادية بسيسو (الأردن)، تمارا سعادة (لبنان)، روجيه أنيس (مصر)، وسيف كسمات (المغرب)– أربعة أماكن عامة في أوسلو في محاولة لخلق حوار بين مشاهد متخيلة، واقع مدينة أوسلو والمدن المقابلة على الطرف الآخر في الجنوب. في غياب علاقة واضحة تربط بين مدن الشمال والجنوب إلا أن مشاهدة هذه الصور تدفعنا إلى التمعن بالتناقضات البيئية والتفكر بمسؤولية مشتركة نحو كوكبنا.

في السنوات الأخيرة كثيراً ما شهدنا مظاهرات في دول عربية مختلفة تعود دوافعها لأسباب تتعلق بالتدهور البيئي والفقر الناتج عن اقتصادات استخراجية ترعاها نظم استعمارية وشمولية وحكومات فاسدة.

يسعى معرض مياه عكرة، كجزء من مهرجان مساحات السنوي للثقافة والفنون العربية إلى خلق فسحات للتحاور بين الفنانين، الأكاديميين، الناشطين والباحثين العرب والنرويجيين المهتمين بالتفكير سوياً بسياسات بيئية عادلة تحمل معها قيماً تضامنية وتحررية تسعى إلى تفكيك وتحطيم البنى الشمولية وايديولوجياتها.

المعرض الفوتوغرافي من إنتاج مساحات بالتعاون مع فوتوغاليريه ومركز الخرطوم للفن المعاصر وآفاق.

الهلال غير الخصيب

Infertile Crescent

Since the beginning of the 19th century, the Middle East has witnessed crucial geopolitical changes. It slipped away from the fists of the Ottoman Empire, only to fall into the hands of British-French colonialism. The region was reconstructed, mapped, and divided into small statelets, which currently form the new, contemporary Middle East. The project Infertile Crescent describes the reality of what was once called the cradle of civilization. Known as the Fertile Crescent because of its crescent shape spanning Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Palestine, and Jordan, among others, today the region is in turmoil. Jordan seems to be the only country that remains relatively stable. As the Syrian crisis enters its 7th year, Jordan reaches a staggering second place in water scarcity, shedding light on the controversial Red-Dead Sea Conveyance, or the Two Seas Canal, built between Jordan, Israel, and Palestine. A 180 km pipeline should carry water from the Red Sea to the Dead Sea. Ecological concerns of disruption in the Dead Sea’s natural ecosystem echo voices of a new era: a vast regional economic Israeli project. Infertile Crescent explores the pipeline route – along sites of the Dead Sea’s ancient legends, where farmers dance around sinkholes of thistle and oases of potash, and along the valley of peace and a desert, yearning to meet the sea. It draws from an old wives tale on the construction of a pipeline – science and local wisdom agree: the next war will be a water war.

نهر النيل… خُلُودٌ مُهَدَّد

Oh Mysterious Nile…Will You Be Immortal!

More than 5,000 years ago, the ancient Egyptians built one of the greatest civilizations in human history, and the Nile River was the cornerstone on which they laid its foundations. The Nile was not embodied by one God but became a particular deity to whom to sacrifice for every seasonal change.

The appeasement of the river throughout history did not prevent famines due to its drying for long periods. The most prominent example is the famine named “Al-Mustansiriya” that occurred during the era of the Fatimid state when the Nile dried up for nearly seven years (1065 AD–1071 AD). The low level of the Nile River, or its dryness, is a terrifying picture that threatens the imagination of the Egyptians. During a period, the Nile had seven branches extending into the delta, five of which disappeared, and only two remain.

Today, the ghost of these frightening images looms on the horizon due to the construction of the Renaissance Dam in Ethiopia and the accompanying possibilities of declining water that reaches Egypt at a time when it suffers from water scarcity.

Environmental and political challenges mark this photographic project where emotional attachment to the river shared by most Egyptians meet possible roads toward a water’s uncertain future.

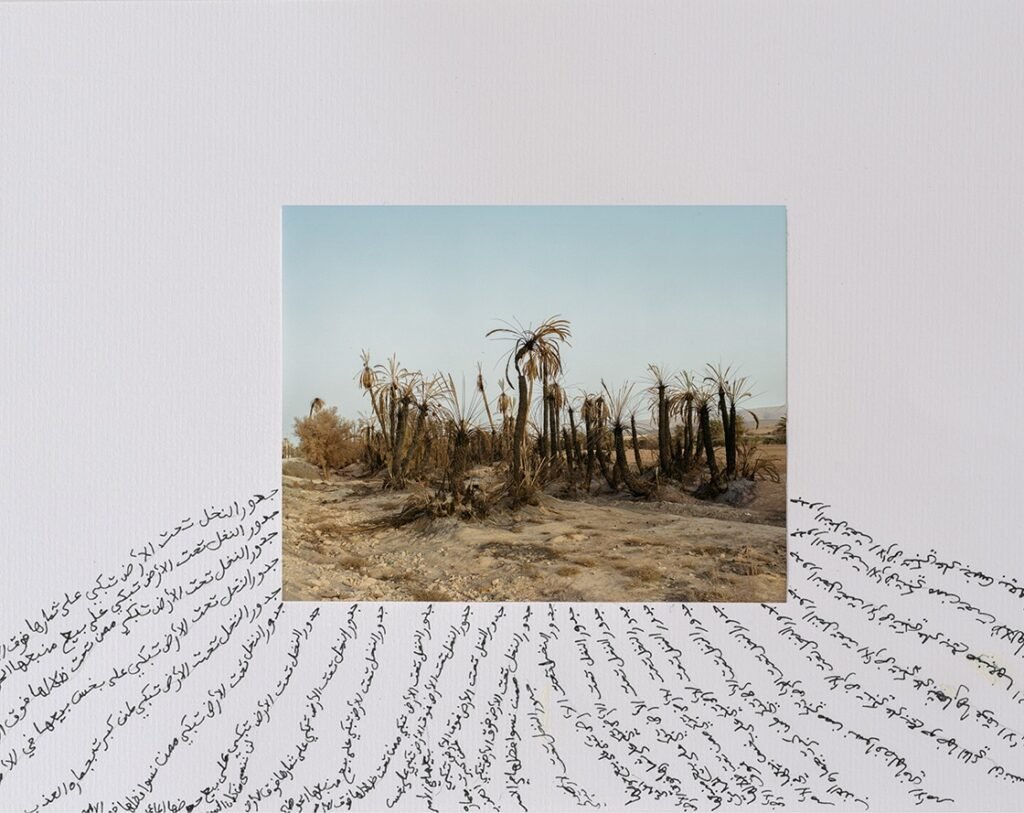

واحة

Waha

For centuries, Morocco’s oases have been home to human settlements, agriculture, and important architectural and cultural heritage, thanks to trans-Saharan trade caravan routes. Today, these oases are home to nearly 2 million inhabitants in Morocco and contribute to the local and national economic and cultural development.

According to official figures, Morocco has lost two-thirds of its 14 million palm trees over the last century. Two-thirds of Morocco’s oasis habitat has vanished — a process accelerated by environmental changes in recent decades. These climate change consequences have an economic toll on the oases’ inhabitants and endanger their livelihoods and subsistence. Despite their best efforts, entire communities abandon their lands and migrate to cities hoping for a better life.

The project asks: how to avoid reproducing orientalist, Eden-like representations of the oasis? How can a photographic work more truthfully express the reality of the deterioration that one observes?

Organic elements such as dry dates, dead skin of palm trees, and soil are “intimately” linked to the spaces through the material of photography. Acid and fire represent the process of degradation that is yet to come.

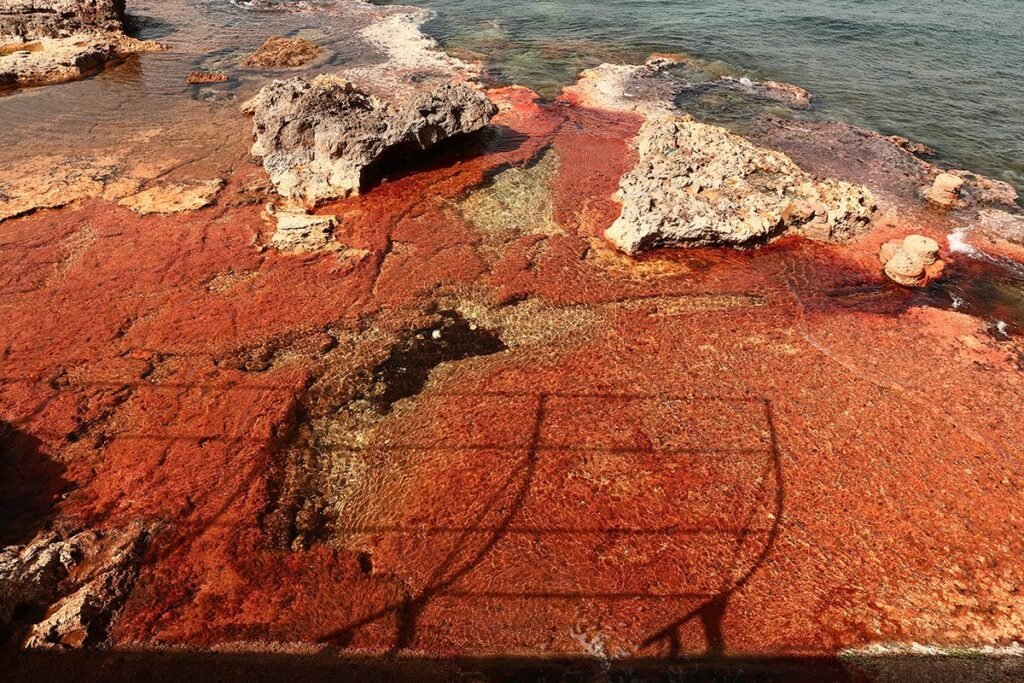

جلد مقشر

Shedding skin

Most of Lebanon’s coast is privately owned today: only a few strips remain accessible to the public. Even these strips of land aren’t available to everyone: they belong to men, a gendered category. They resist. They reclaim the coast by taking up space and tanning all day.

The project tackles such fascination with a gendered space and to whom resistance is permitted: men hanging around, unclothed, in the middle of the city and appropriating such space through their bodily presence patriarchally driven. Directly and indirectly, the such claim makes women and gender nonconforming bodies feel out of place, intimidated, and uncomfortable. The photographer, bodily expressing such otherness, challenges such space by entering dressed and with a camera.

The Shedding Skin project explores the relationship between men, the space they occupy, and the photographer against the backdrop of sun, sea, and a country constantly tainted by economic and political collapse.